Gilsonite Utah

Gilsonite Utah

Definition and Description

Gilsonite is a naturally occurring, solid, black, lightweight organic material that originates from the solidification of petroleum. The dull, black appearance of weathered gilsonite resembles coal, whereas the surface of freshly broken gilsonite is shiny and resembles obsidian. Gilsonite is distinguished by its solubility in organic solvents, low density, and brown streak when rubbed on paper. Solid hydrocarbons like gilsonite are called asphaltites and are found in oil-bearing sedimentary basins, commonly as veins associated with oil shale. There are dozens of asphaltite deposits around the world and many of them have been mined; however, the gilsonite variety is relatively rare and the large size of the Utah deposits makes them unique. Uses Gilsonite has hundreds of industrial applications and is used by companies all over the world. Gilsonite is added to oil- and gas-well-drilling mud to stabilize the borehole and decrease friction; it is also used in oil well cement. Gilsonite and gilsonite-derived resin wet and disperse carbon black pigment in printer’s ink and bind pigment to the newsprint so it does not rub off. Addition of powdered gilsonite to asphalt paving mixes produces a more durable road surface. Paint-like mixtures of gilsonite, solvents, and other additives are used to coat and seal asphalt pavements like driveways and parking lots. Gilsonite is also used as an adhesive and waterproofing agent in the manufacture of roofing felt. Addition of gilsonite makes some paint and wood stain formulations more durable. Gilsonite is added to iron foundry molding sand mixtures to produce a smoother finish on the cast item and make it easier to unmold. Small amounts of gilsonite are used in fireworks and to manufacture high-purity carbon electrodes.

Gilsonite, one of Utah’s earliest mined industrial minerals, is currently experiencing increased interest by the oil and gas industry, which has resulted in a significant increase in development of the resource. The Uinta Basin of eastern Utah hosts the world’s largest deposits of Gilsonite and is the only place where gilsonite is economically produced in large quantities. Gilsonite has a wide variety of industrial applications and is used by companies worldwide. Major uses for gilsonite include ink and paint, and as a performance additive for the foundry and asphalt industries, but the oil and gas industry has developed as a growth market for gilsonite due to the expansion of various applications in well drilling.

Gilsonite is a geologically interesting and economically significant resource, and its wide range of uses has changed over time with new technology and industrial needs. Gilsonite’s unique properties make it important for many oilfield drilling fluid products and the recent boom in oil and gas development has increased demand. When gilsonite is added to oil-based drilling Muds and water-based drilling fluids, it partially melts or deforms, plugging off micro fractures in the rock and smearing the inside of the well bore to make a tight, tough filter cake that prevents fluid loss. The dissolved gilsonite also increases drilling fluid viscosity, providing lubrication, and together with the sealing off and stabilization of problem rock around the well bore, helps prevent the drill pipe from getting stuck in the well. Gilsonite is also used in cementing fluids as a lost-circulation material due to its plugging and binding properties, and as a slurry density reducer in some specialty cementing fluids.

Gilsonite is a member of the asphaltite group of hydrocarbon bitumens, and forms a swarm of subparallel, northwest-trending, near-vertical, laterally and vertically extensive veins in the Uinta Basin of Utah and Colorado. Gilsonite was generated from the Mahogany oil shale zone in the Parachute Creek Member of the Eocene Green River Formation and is hosted in the Tertiary-aged (about 57 to 36 million years old) Wasatch, Green River, Uinta, and Duchesne River Formations. The veins range from sub-inch to as much as 22 feet wide and formed in two stages associated with thermal maturation of the Mahogany oil shale. High pressures deep in the Uinta Basin led to the expulsion of large quantities of hot water from the oil shale rocks, which hydrofractured the overlying and underlying strata. Subsequently, thick, liquid gilsonite was expelled from the oil shale source beds, forcing open the existing fractures in the overlying and underlying strata. The Gilsonite later solidified in these fractures, probably primarily through cooling. The Gilsonite Utah veins are widespread across the Uinta Basin, extending from Rio Blanco County in western Colorado to Duchesne County in eastern Utah.

Gilsonite has a long, colorful mining history dating back to the late 1800s. Gilsonite, named after Samuel H. Gilson, was discovered in the 1860s in Utah. Gilson was not one of the original discoverers, but his enthusiastic development and promotional efforts linked the material to him, and the name gilsonite further solidified in common usage when an early mining company adopted and trademarked the name. The first regular shipments of gilsonite began in 1888, from veins in the Fort Duchesne area. Early gilsonite mining was predominantly by open-cut mining with picks, shovels, and horse-powered hoists (for more background see Survey Notes v. 36, no. 3, July 2004).

Gilsonite Utah Mine

Location and Extent

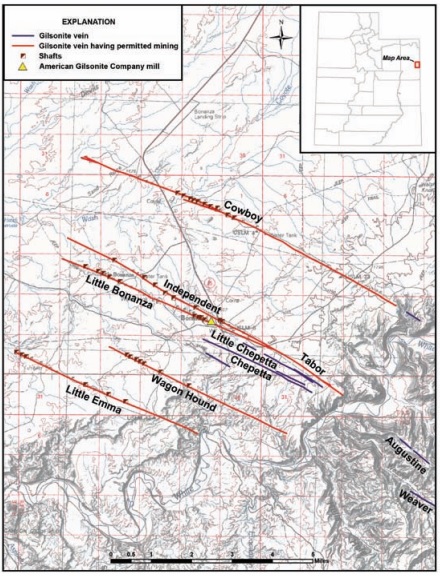

Gilsonite Utah is found in dozens of long, vertical, northwest-trending veins in a 60-mile by 30-mile area of the Uinta Basin (see figure). The veins vary in width from fractions of an inch to almost 18 feet but average about 3 to 6 feet. The continuity of the veins is impressive; they stretch in long, straight ribbons across the hills of the Uinta Basin. These veins are commonly several miles long and the longest vein system in the basin extends 24 miles. The Gilsonite veins are also vertically continuous for hundreds to as much as 2,000 feet or more, commonly with only small variations in vein width. The veins are usually rooted in the Green River oil shale, so they are more vertically extensive to the northwest where they are not as deeply eroded. The oilshale depth contours on the accompanying figure indicate the potential depth of the veins.

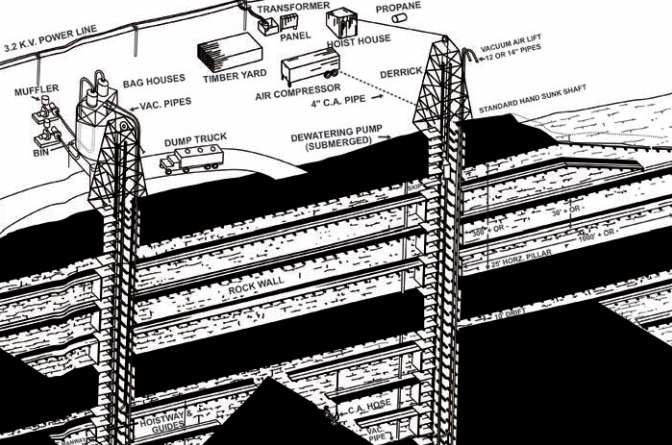

Historically, mining occurred at various veins and locations in the Gilsonite field, but it is currently concentrated on the widest known veins around Bonanza, Utah. Permitted mining in this area occurs on the Cowboy, Independent, Little Bonanza, Wagon Hound, and Little Emma veins. All the gilsonite produced today from the Uinta Basin is by underground mining methods. Current mining consists of two major phases: (1) shafts are sunk at regular intervals along the veins, and (2) drifts and slopes are then extended laterally from the shafts. The top 30 feet of the gilsonite is not mined for safety and reclamation reasons. Gilsonite mining is labor intensive, because of its unusual mode of occurrence in narrow (down to 18 inches wide), deep, vertical veins; and the explosive hazards associated with gilsonite dust. The mining of the ore is still done by hand, using air-powered chipping hammers to carefully break the gilsonite while avoiding contaminating the ore with broken wall rock, since product purity is important to customers. The broken ore enters a vacuum tube at the bottom of the underground mined area and is air lifted to the surface, where it is deposited into a bag house next to the shaft headframe and then trucked to a plant for processing.

American Gilsonite Company (AGC) and Ziegler Chemical and Mineral Company are the only companies that mine and process gilsonite at their operations in southeastern Uintah County. Gilsonite Utah production in 2012 was about 82,000 short-tons, with AGC responsible for most of that production. Gilsonite Utah production in 2012 is valued at approximately $89 million, at an average price of about $1085 per short-ton (as reported by the U.S. Office of Natural Resources Revenue). Gilsonite value has significantly increased from oilfield demand, and gilsonite sales to the oilfield market have increased over 150% since 2009. In response to increased demand, AGC has initiated an approximately $20 million investment program to open new mines, explore new mine development methods, develop strategic long-term reserves, and continue investment in health and safety. AGC expects to double its current production capacity in the near future to satisfy customer demand and has opened three new mines in the last 18 months, with five more under active development.

Even though significant amounts of the approximately 45-million short-ton original gilsonite resource have been mined, millions of tons of the valuable resource still remain. This resource tends to be in the deeper parts of the veins and in thinner, more remote veins that will likely be more expensive to mine than veins mined in the past. Recent mapping by the Utah Geological Survey (Special Study 141) of the gilsonite deposits in the Uinta Basin has located and described many of the more remote veins, which were previously only vaguely know. At the planned increased production rate, gilsonite could continue to be mined in the Uinta Basin for decades, ensuring a steady supply to world markets of this unique and valuable Utah resource.

Geologic Setting and Origin of Gilsonite Utah

Gilsonite Utah veins are found in Tertiaryaged (about 57 to 36 million years old) sedimentary formations in the Uinta Basin. These formations, in order from oldest to youngest, are the Wasatch, Green River, Uinta, and Duchesne River Formations. The veins are best developed in the thick sandstones of the upper Green River and lower Uinta Formations and tend to split and be less continuous in mudstone, marl, and discontinuous channel sandstones. In the Wasatch Formation (below the oil shale), gilsonite is exposed only in veins at the easternmost edge of the gilsonite field where the strata are most deeply eroded.

Deformation (thrust faulting and downwarping) associated with the Sevier/Laramide mountain-building episode formed the Uinta Basin. This topographic basin was occupied by lakes of various sizes over millions of years. Large amounts of organic material accumulated on the lake bottom, particularly during one period when Lake Uinta reached its maximum areal extent in the basin. Later, heat and pressure of burial changed the organic-rich sediment into the thick oil shales of the middle to upper Green River Formation. Burial of the oil shale generated water and hydrocarbons that were expelled, fracturing the surrounding rock. The escaping water deposited minerals on the walls of the fractures. Viscous Petroleum was later extruded into the fractures, forcing them open, filling associated sills, and in some areas saturating wall rock. The viscous hydrocarbons later solidified into gilsonite.

Development History of Gilsonite Utah

The first documented mining of gilsonite was in 1868 when a blacksmith asked local Native Americans to find coal for his forge. The gilsonite that they (mistakenly) brought him reportedly melted, caught fire, flowed out of the forge, and almost burned down the blacksmith shop. This unusual material also caught the attention of many of the new immigrants in the area who staked claims on the veins even before it was clear what the material was, or how it might be used. Two early prospectors, Bert Seaboldt and Samuel Gilson, experimented with the gilsonite, developed uses for it, and secured financing for development. Gilson’s enthusiasm and promotional ability resulted in the newly discovered material being named after him (it’s formal mineralogical name is uintaite).

The first regular shipments of gilsonite utah began in 1888, from veins in the western part of the gilsonite field. The Gilsonite was shipped 60 miles south by wagon from Myton to the railroad at Wellington. Early development was an intense period marked by exploration, mining property consolidation, negotiation and conflict with Native Americans and government agents, and lobbying in the U.S. Congress for changes to Native American Reservation boundaries. By 1903, the Gilson Asphaltum Company (predecessor of the American Gilsonite Company) controlled most of the gilsonite resource, including large veins that had been discovered in the eastern part of the basin. In 1904, Gilson Asphaltum constructed the now defunct, narrow-gage Uintah Railway from the eastern part of the field (near Rainbow, Utah) to the Denver and Rio Grand Western railroad in Colorado. The improved transportation helped the industry expand and develop new markets. In 1935, Gilson Asphaltum moved its operation north from the Rainbow area to a new mine and processing plant at Bonanza and switched to truck transportation.

The Gilson Asphaltum Company reorganized, and in 1948 became the American Gilsonite Company that was jointly owned by the Barber Oil Company and Standard Oil of California (now ChevronTexaco Corporation). The company’s research led to the use of gilsonite as a refinery feedstock to produce gasoline, high-purity electrode carbon, and other products. By 1957, American Gilsonite had constructed a refinery in Gilsonite, Colorado, that was connected to their Bonanza plant by a 72-mile-long slurry pipeline laid along the abandoned Uintah Railway route. Gilsonite production rose to about 470,000 tons in 1961 as a result of the pipeline and refinery. The gasoline was marketed under the trade name Gilsoline. Cars fueled with Gilsoline were reportedly easy to identify because their exhaust had a characteristic odor. The company sold the refinery in 1973 and redirected their marketing efforts to nonfuel uses of gilsonite. In 1981, Chevron purchased Barber Oil’s share of American, and in 1991, Chevron sold their interest. Today, the American Gilsonite Company remains the world’s largest gilsonite producer.

Small independent companies have long competed with the American Gilsonite Company and its predecessors. Between 1952 and 1962, G.S. Ziegler and Company, originally a gilsonite customer, purchased and operated the properties of many of the small independents and changed its name to the Ziegler Chemical & Mineral Corporation. They have long maintained a plant and office at Little Bonanza and have been a substantial gilsonite producer for more than 40 years.

Lexco, Inc. began operations in 1988 and constructed a plant and office southeast of Fort Duchesne. They have mined and shipped ore from veins in the south-central part of the gilsonite field.

The original in-place gilsonite resource was estimated at 45 million tons. Most of that ore has been extracted; since 1907 gilsonite production has typically varied between 20,000 and 60,000 tons per year with a spike to 470,000 tons per year in 1961 when American Gilsonite Company’s refinery was operating. Additionally, some of the remaining in-place resource cannot be mined due to geologic and engineering problems. In 1980, an American Gilsonite employee estimated that about 5 million tons of mineable reserves remained in the basin. However, the potential for discovery of new veins, as well as increased resource estimates for small, known veins, may increase gilsonite resource values in the basin.