gilsonite history

Gilsonite history

Gilsonite or Natural Bitumen was first discovered in the United States of America in the 19th century. It’s confirmed that the Native Americans who lived in the state of Utah were familiar with this material, yet there was neither commercial nor scientific use of it until the pioneers entered the Continent.

The discovery was made by Samuel H. Gilson who was a marshal in the Utah area while attending a horse trading business in the livestock market. He detected (or was led to by a local) a shiny black raw material, which eventually after examination at the Columbia College School of Mines in 1865, proved to be over 95% made of hydrocarbons.

Throughout the years, Mr. Gilson made lots of efforts to use the newly discovered item for different applications, in order to make commercial benefit out of it, yet mostly unsuccessful. His ultimate achievement was selling his company under his own name to a firm in Saint Luis which was then renamed to The Gilson Asphaltum Company.

In later years, different commercial purposes of Gilsonite were found and applied. Some companies developed more advanced usage such as Printing Inks and Drilling Mud Additives and some failed significantly including John Kelly. His approach was to use Gilsonite instead of coal. Also, American Gilsonite Company failed to extract Diesel from Gilsonite while having it moved through pipes from Utah to Colorado.

Ancient texts that date back to the late 3rd millennium BC, as well as manuscripts of Greek and Roman historians such as Xenophon, Ptolemy, Herodotus, Plutarch, Strabo, and Pliny, pointed out the presence of bitumen mines and springs in the Middle East. These deposits start in a vast area along the Indus in India and continue as a crescent to Sinai Peninsula in Egypt and the Dead Sea in Jordan. Most of the bitumen springs are concentrated in the southwest of Iran and Mesopotamia.

In Mesopotamia, the use of bitumen dates back to prehistoric times. In Iran and especially in the west of Iran, bitumen is found in abundant. From the Neolithic period, people living in this region used this material in different applications such as plating dishes, floors, and walls of houses, making decorations as well as in medicine and veterinary medicine for treatment of infectious diseases, rheumatic pains, and bone fractures. There are thousands of oil fields in the Middle East. As a result, bitumen seeps up from underground with water or purely in large scales. A most significant bitumen spring is found in Dehloran. In this spring, which looks like a small lake, the molten bitumen flows with water. It can be said that the first experience of the Neolithic human with bitumen was such springs and lakes. Since bitumen is sticky and sometimes smelly, the Neolithic human was extremely cautious in approaching it and called it the pit of death. After this period, they discovered properties of bitumen such as impermeability to water, adhesion, softness, ductility, and the ability to combine with other materials. They gradually learned various applications of bitumen.

The ancient use of Bitumen are:

- Sealing the seams in clay drains of the inner wall in Chogha Zanbil ziggurat in Susa, which was built in 1250 BC;

- Mummifying bodies, especially by the Egyptians;

- Using as fuel and in catapult shot, by Iranian;

- Paving the chariot road in Rome;

- Tarring potteries;

- Using in Baghdad batteries, with about two thousand years old.

Bitumen was discovered in the early 1860’s in Utah, America. But it was not known until the mid-1880’s that Samuel H. Gilson began to promote it as a waterproof coating for wooden pilings, as an insulation for wire cable, and as a unique varnish. Gilson’s promotion of the ore was so successful that, in 1888, he and a partner formed the first company to mine and market Gilsonite on a commercial scale.

The first authentic commercialization of Gilsonite was launched by Chevron. They established the American Gilsonite Company in order to uncover workable applications for the natural bitumen and also locate stable markets for the product. That resulted in a successful business for 100 years until a dramatic hit at 2012 when oil prices around the globe started falling.

Gilsonite history in 1906

In 1906, Utah’s Governor Dern in referring to the State’s hydrocarbon deposits, which he claimed surpassed “in variety, purity, and extent all other recorded occurrences,” said further that “transportation facilities alone are lacking to make the deposits a bonanza of wealth. . . In this comparative.

Gilsonite history of Utah

modest appraisal of Utah’s potential hydrocarbon industry, the point of need for better transportation facilities was well taken and was applicable not only to the State of Utah in general but to the Uinta Basin in particular. No one was so much aware of the need for improved means of transporting mineral products as the residents of the Uinta Basin themselves; and as early as 1895, only seven years after the Gilson Asphaltum Company of Missouri had begun operating the St. Louis Mine, there were many hopeful expressions about a major railroad company constructing a line through the Uinta country. Predictions of soon-to-be-built railroads were almost unfailingly accompanied by predictions of fabulous industrial growth in the Ashley and Uinta Valleys.

The Utah Asphaltum and Varnish Company, which owned extensive asphalt deposits on the ridge southwest of Vernal, claimed that they would, when the railroad arrived, build large paint and varnish factories in Ashley Valley and employ a great number of people. Further, they envisioned the valley becoming “one of the greatest manufacturing centers in the West.

Gilsonite History- Development History

The first documented mining of gilsonite was in 1868 when a blacksmith asked local Native Americans to find coal for his forge. The gilsonite that they (mistakenly) brought him reportedly melted, caught fire, flowed out of the forge, and almost burned down the blacksmith shop. This unusual material also caught the attention of many of the new immigrants in the area who staked claims on the veins even before it was clear what the material was, or how it might be used. Two early prospectors, Bert Seaboldt and Samuel Gilson, experimented with the gilsonite, developed uses for it, and secured financing for development. Gilson’s enthusiasm and promotional ability resulted in the newly discovered material being named after him (its formal mineralogical name is uintaite).

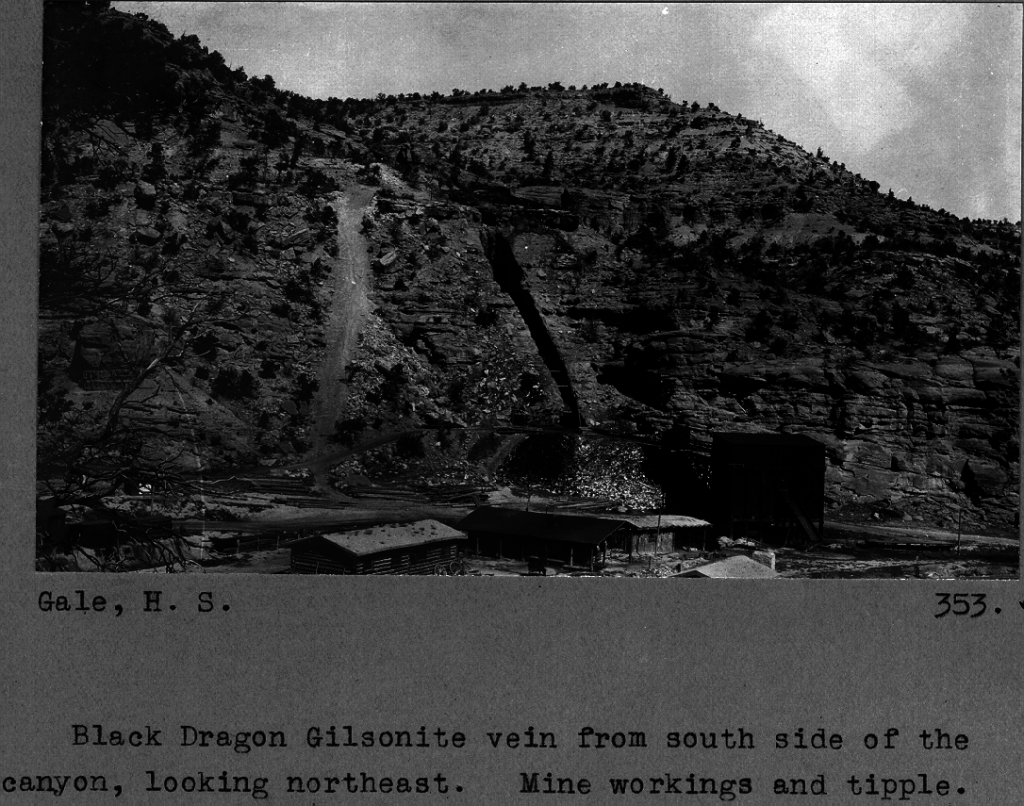

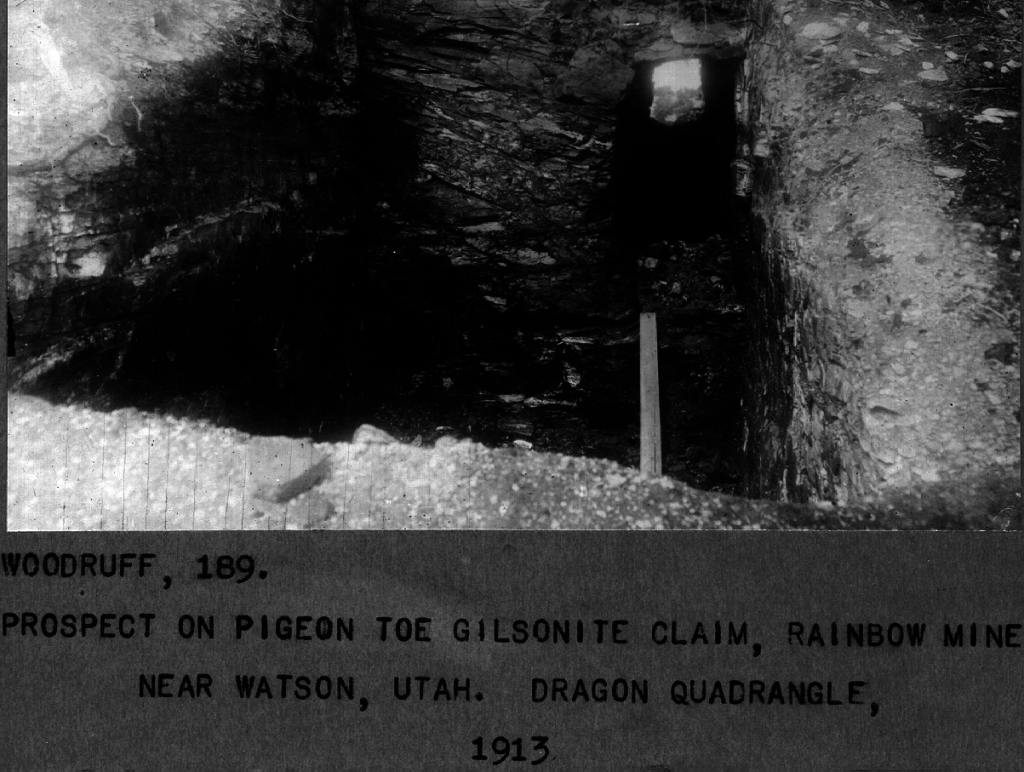

The first regular shipments of gilsonite began in 1888, from veins in the western part of the gilsonite field. The gilsonite was shipped 60 miles south by wagon from Myton to the railroad at Wellington. Early development was an intense period marked by exploration, mining property consolidation, negotiation and conflict with Native Americans and government agents, and lobbying in the U.S. Congress for changes to Native American Reservation boundaries. By 1903, the Gilson Asphaltum Company (predecessor of the American Gilsonite Company) controlled most of the gilsonite resource, including large veins that had been discovered in the eastern part of the basin. In 1904, Gilson Asphaltum constructed the now defunct, narrow-gage Uintah Railway from the eastern part of the field (near Rainbow, Utah) to the Denver and Rio Grand Western railroad in Colorado. The improved transportation helped the industry expand and develop new markets. In 1935, Gilson Asphaltum moved its operation north from the Rainbow area to a new mine and processing plant at Bonanza and switched to truck transportation.

The Gilson Asphaltum Company reorganized, and in 1948 became the American Gilsonite Company that was jointly owned by the Barber Oil Company and Standard Oil of California (now ChevronTexaco Corporation). The company’s research led to the use of gilsonite as a refinery feedstock to produce gasoline, high-purity electrode carbon, and other products. By 1957, American Gilsonite had constructed a refinery in Gilsonite, Colorado, that was connected to their Bonanza plant by a 72-mile-long slurry pipeline laid along the abandoned Uintah Railway route. Gilsonite production rose to about 470,000 tons in 1961 as a result of the pipeline and refinery. The gasoline was marketed under the trade name Gilsoline. Cars fueled with Gilsoline were reportedly easy to identify because their exhaust had a characteristic odor. The company sold the refinery in 1973 and redirected their marketing efforts to nonfuel uses of gilsonite. In 1981, Chevron purchased Barber Oil’s share of American, and in 1991, Chevron sold their interest. Today, the American Gilsonite Company remains the world’s largest gilsonite producer.

Small independent companies have long competed with the American Gilsonite Company and its predecessors. Between 1952 and 1962, G.S. Ziegler and Company, originally a gilsonite customer, purchased and operated the properties of many of the small independents and changed its name to the Ziegler Chemical & Mineral Corporation. They have long maintained a plant and office at Little Bonanza and have been a substantial gilsonite producer for more than 40 years.

Lexco, Inc. began operations in 1988 and constructed a plant and office southeast of Fort Duchesne. They have mined and shipped ore from veins in the south-central part of the gilsonite field.

The original in-place gilsonite resource was estimated at 45 million tons. Most of that ore has been extracted; since 1907 gilsonite production has typically varied between 20,000 and 60,000 tons per year with a spike to 470,000 tons per year in 1961 when American Gilsonite Company’s refinery was operating. Additionally, some of the remaining in-place resource cannot be mined due to geologic and engineering problems. In 1980, an American Gilsonite employee estimated that about 5 million tons of mineable reserves remained in the basin. However, the potential for discovery of new veins, as well as increased resource estimates for small, known veins, may increase gilsonite resource values in the basin.